In early June 2025, we received the sad news that Michael Cooper NEAC had passed away. His subtle semi-abstract landscapes and pared-back portraits have graced the walls of our annual exhibitions since his election in 2004.

In this tribute, fellow NEAC member Paul Newland shares his stories and touching memories of his friend Mike (with an amusing bonus story at the end from Peter Brown).

The Book of Tobit is an unusual influence for a 20th-century artist. At five or six, Mike was taken to the doctor, ill from some eating disorder. He saw a print on the wall and was told that it was Tobias and the Angel, a scene from the book. This angel is the Archangel Raphael, whose primary duty is healing. On the way out of the surgery, he picked up a badge fallen from an airman's uniform – shiny, perhaps stitched – a pair of wings and an oak wreath.

He recovered, and the image assumed intense personal meaning. Its association with healing was inescapable. The narrative was popular in the early and late Renaissance period. An ink wash drawing in Mike's archive commemorates Adam Elsheimer's version – perhaps the most eloquent of them all.

Mike's artistic training was unusual by NEAC standards. At 15, he was out of school and into work. It was Birmingham, with thriving jewellery and metalworking trades, and he was apprenticed for some years to an uncle, a silversmith.

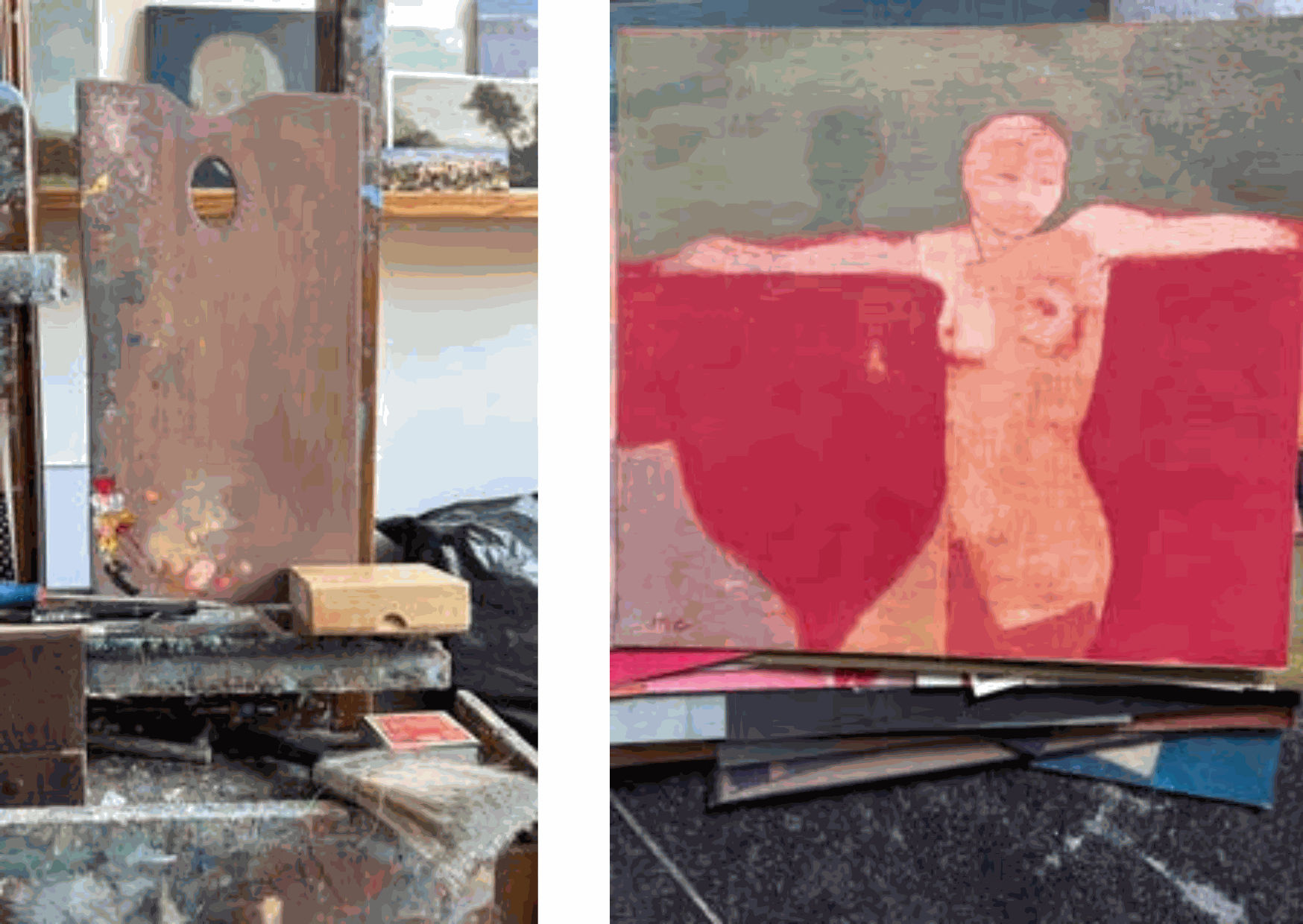

Later, the family moved south, and Mike found work with Bertie Boast – picture restorer, cartoonist (and hell raiser) of Brighton. This was a sound way into the historical crafts of painting and restoring – make your own mahogany palette, your own mahl stick, study techniques. Training even included serious repair work on Sickert's Brighton Pierrots, damaged by misadventure in the restorer's workshop.

Delicacy, intricacy, and craftsmanship were likely to become hallmarks of his practice, and certainly came in handy when producing 'potboilers' at the onset of his career. Some 'antique' dealers in London found simulations of English hunting or coaching scenes (and the occasional big cow or pig) to be profitable, and Mike's skills and speed were indispensable. In the studio of his later years, a modest little marked cardboard box contained photos of these nostalgic coaching or hunting scenes, plus photos of an occasional fine copy of a Claude or a Mantegna.

Hill Curve and Cloud (oil)

But throughout this time, he nurtured a feeling and a need for painting, sustained by his own vision of the natural world and supported by reference to historical figures, especially William Blake and Samuel Palmer, and to certain landmark exhibitions. We had both seen the great survey exhibition 54–64: Painting and Sculpture of a Decade at the Tate Gallery in 1964. If you weren't in the informed art school milieu, it opened your eyes, gave a sense of release, possibility and movement. All these years later, there was the catalogue on his studio shelves.

I saw these shelves for the first time in perhaps 2010. I had moved to Sussex a year or two previously and wanted to meet this fellow NEAC member. From the street, you’d never know the secluded house and studio were there. They could only be entered through another property's garden. Very 'Lewes'.

An inscription over the stone fireplace reads “1744”, the date of this extension from a medieval structure next door. Glass cases displayed flints – arrowheads, scrapers, knives – knapped in this area of East Sussex in the Mesolithic period and collected without difficulty, if you know the spots – and other fragments of local origin. Periodical publications by the Sussex Archaeological Society filled one bookshelf.

This corner of Lewes is rich in historical remains and associations, and the building of a new studio uncovered artefacts and garden architecture of far earlier times. Talk would range across these matters – painting problems, trips to Italy, music (a lifelong love), and the vicissitudes of life.

A major venture, dating from well before I knew Mike, was the acquisition of the defunct Star Brewery near Lewes Castle. He set up and managed the group behind the purchase. Its various floors and divisions were converted into studio spaces for craftspeople, visual artists, photographers, a framer, and so on. This made a considerable mark on the cultural landscape of a town where property values and rents are high, and it left many people with a sense of gratitude for his vision and perseverance. I think he also came to relish the struggles with the local authority – his stories of their obtuseness and philistinism were legion.

Evening Landscape (oil)

Much consideration was given to the works Mike would submit for the NEAC annual show, and I watched with fascination their progress: the imaginative craftsmanship in the overlaying of colours, the rearrangements of forms, the augmenting of an image's emotional depth.

Nicolas de Staël was an artist for whom he felt great admiration, a man who sought constantly to do justice to our perceptions of space and light. One day, we studied the magnificent array of his works in the museum at Antibes. A quotation from one of de Staël's letters comes to mind now, remembering our friend and colleague Michael Cooper:

“True painting always attempts to include all aspects … the impossible addition of the present, past and future.”

Still Life (oil)

And finally, we'll leave you with an amusing memory of Michael from Peter Brown PPNEAC . . .

I loved Michael’s paintings. When he was first elected, I remember thinking, “What a breath of fresh air.” It sounds a bit naïve, but I thought, “How modern!” I think it was the colour and design.

He was very entertaining and I loved seeing him at the annual exhibitions. When Ken Howard was President, he held a members’ party in his Chelsea studio. We all got fairly sozzled as we wandered in awe at the paintings and this incredible space – as the wine flowed.

Michael and I decided to have a little look through Ken’s plan chests. A bit cheeky, but it was busy and we thought he wouldn’t notice or indeed mind. Unfortunately, as we opened one of the drawers full of drawings, I managed to knock my glass of red wine into it.

Utterly horrified at what I'd done, Michael shrieked with laughter, unable to contain his fits of giggles and was absolutely no help at all, pointing out I’d probably caused tens of thousands of pounds of damage. I mopped it up as best I could and then, in my drunken idiocy, decided not to tell him. Of course, in the morning I phoned Ken up to let him know. He checked the drawers and said, “It looks fine to me, Pete.”

Michael and I could never understand how I got away with that.

Two Pale Bathers, Antibes (oil)

For further information and images of his paintings, see Michael Cooper's NEAC artist profile page